Catching Up With Air-Edel's Patrick Neil Doyle

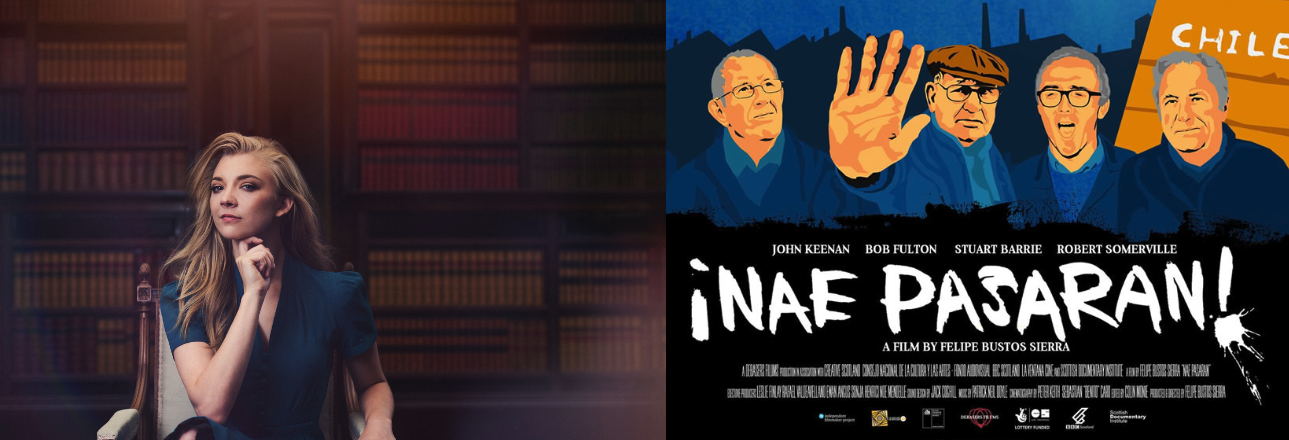

Air-Edel’s Patrick Neil Doyle has had an exciting year in composing, marked most recently by the release of the ‘Harry Potter: A History of Magic’ audio book, narrated by Natalie Dormer, and two BAFTA nominations for Scottish feature documentary ‘Nae Pasaran’. We caught up with him to learn more.

Air-Edel Records recently released your soundtrack for the historical feature documentary ‘Nae Pasaran’, which tells the story of the Rolls-Royce factory workers in Scotland who refused to carry out vital repairs to the Hawker Hunter jet engines used by General Pinochet, and saved thousands of lives in Chile during the 1970s. Were you familiar with the story before you began scoring for the project?

I knew of the Rolls-Royce factory in East Kilbride, and I have friends who know former Rolls-Royce factory workers, but neither I, nor my friends, nor those who worked in the factory during the 1980s had ever come across this unbelievable story until this film. You’ll see from the documentary that the director, Felipe Bustos Sierra, has done a tremendous job in finding out the truth about events, providing magnificent archive footage, and leaving no stone unturned in shedding a light on the lives of all those brave individuals involved in standing up to General Pinochet’s military regime.

All of my family live outside Glasgow, very close to where the employees honoured in this documentary are from, and how they interact with each other on screen is exactly how my whole family in Scotland laugh and joke with each other. I had this overwhelming sense of pride when watching the film for the first time, because not only were these humble men from the country of all my relatives, but they were so similar to my family that I felt they could have actually BEEN my relatives. In another circumstance this might have been my uncle, my grandad, my grandad’s brother, modestly retelling how they helped to bring down such a brutal dictatorship, and with that thought in my mind I couldn’t hold back my emotions when watching the film and when composing the music for it.

This was your first time collaborating with Felipe, and your first documentary – how did this differ from composing for feature films and TV series?

Felipe and I decided early on that Nae Pasaran could definitely take a pretty rousing and emotional orchestral main theme that returns again and again at the important moments of the film. I wouldn’t say that this was necessarily native to documentary film scores but the film had some very powerful moments with less dialogue that certainly called for a fuller sound than something composed purely for the purpose of underscore. There were beautiful long shots of the Chilean Andes, Santiago skyline, and amazing sequences of the Scottish landscape, so the emptier soundscape for these moments had a lot of room for music. This felt like something one might not expect from a documentary, but it fit perfectly.

The arch of the film and the journey of its characters felt scripted very much like a regular feature, and so my approach was more or less the same, whilst also accommodating for slightly more dialogue. Something I found more effective at times in this film was deciding NOT to have music at certain points. This allowed the film to breathe and the story tell itself. Going into writing the score for this documentary, I spotted for a lot more music than I actually ended up writing, and that is because after tackling a lot of the major music cues it was clear there wasn’t the need for almost constant underscore, which for a lot of documentaries is quite normal. However, even with less music than I might usually have gone about composing, it didn’t make the music any less important. If anything, creating the right music for this documentary felt even more important – one too many layers and you cannot hear the dialogue, or the music could stick out too much. Getting the right balance took a lot of precision.

You mentioned previously that you drew your inspiration from the landscape and the brave individuals the documentary focusses on. How did this help you to create the sound world of the score?

It helped in many ways along the way. After watching the film and seeing all the shots of the landscapes in both Chile and Scotland, I knew that there was a folk music element that would be great to hear in the music. The use of solo guitar and flute worked tremendously well for both the Chilean and Scottish folk element. I also listened extensively to Chilean musicians of the time, such as Víctor Jara and Los Jaivas, pinpointing that in both the folk music of Scotland and South America it is quite common to have an improvisatory approach and at points hear the melody in unison, so these effects appear a few times throughout the score.

I had an extremely visceral response when first listening to the story of both the Scottish factory workers and the formidable Chilean civilians who suffered during the atrocities, so when approaching the music, I already knew the type of emotion I wanted to capture. One of the most Celtic cues, sounding to me like a string arrangement of an “auld scots sang”, is just called Pride, because that’s genuinely all I felt that morning when writing this piece. Another instance where the music was uniquely influenced by the individuals on screen was during the sequence accompanied by the track entitled The Machine. This was the first time the guys in the factory talked in detail about the events that lead to the engines being blacked, and each of them contributed with a different part of the story, reminiscing and re-tracking the events. I had a note from Felipe that this was to feel like the band was getting back together, so in the music I decided to take that note far more literally and I gradually brought in different members of the “band” on their respective instrument throughout the piece. It was a lot of fun to write and I’m now desperate to ask them all if they ever formed a band, or if they do in the future what it might be called…

The score was recorded using musicians in Budapest at TOMTOM and London musicians in our studios. Is this a way you’ve recorded before, and do you find this two-step process a useful way of working?

I’ve recorded this way a few times before, ever since my first score for The Legend of Longwood, and I find it beneficial in many ways. Firstly, the musicians and recording team at TomTom studios are fantastic to work with, and are more than happy as part of the package to source all their brilliant musicians and print sheet music ahead of and during the sessions. Also, like many others, I like to start working as early as possible in the morning, so the fact that Hungary is one hour ahead means we can start at 8am UK time (9am Budapest time), making it feel like we are gaining an hour of recording time our end if we have a soloist coming in to the UK recording studio that evening – it’s a small thing but it makes a big difference gaining some time right at the end of the scoring process.

Budapest is a wonderful city, so whenever possible and if schedules permit I would absolutely take the opportunity to go out there for the recording sessions. I think you gain a lot from working with the players face-to-face, so that is why in most circumstances when we are sat in a London recording studio, it is a lot more effective to record the soloists there. You are able to more easily discuss styles of playing, tweaks in the sheet music, or reference points to hit on screen. It was a privilege to have both Karen Jones (flute) and John Paricelli (guitar) come in and perform on the score for Nae Pasaran – they were truly marvellous to work with.

Alongside scoring ‘Nae Pasaran’ you have also been composing for the upcoming non-fiction audio book ‘Harry Potter: A History of Magic’, narrated by Natalie Dormer. How does composing music for an audio book differ from scoring for other platforms?

Composing music for Harry Potter: A History of Magic this summer has been incredible. It was the first time I had written music for an audio book and I was thrilled to get to compose for such a wonderful project. The book is made up of eight main chapters spread out into several parts. The chapters are the subjects of study at Hogwarts, and I composed a different musical theme for each subject, provided musical underscore to accompany the dialogue and created appropriate musical transitions to add a nice flow to the audiobook overall. Although this was a very new format for me, I found that I was pulling from certain composition techniques I have used for theatre before, such as having passages of the music including a vamp with an applicable musical ending.

Along with being sent the recordings of the audio book to compose for, I was given the script to read through as well. I found that when reading the audio book written out I was using the same part of my imagination to conjure up the images as I was to create the music. Going from book form to purely audio form was a new experience for me and a highly enjoyable one. I have not composed for radio before but I imagine that there are a lot of similarities.

The audiobook takes stories of real-world magic from across Europe, China and beyond, and focusses on how some of its ancient objects, manuscripts and spells influenced the Harry Potter stories. Did these cultural factors influence your score in anyway?

Absolutely. Specifically for the chapter Care of Magical Creatures, where I used the Bansuri and Sarangi to conjure up the feeling of far off lands with amazing animals and magical mysteries to be discovered. Other instruments that worked well to produce an eclectic sound in the music of the audio book were the Bodhran Drum, Zither, Accordion and Tibetan Singing Bowls. As well as this, I made great use of the traditional instruments of the symphony orchestra in order to tap into that magical sound of Harry Potter music that would be odd not hear for an audio book of this nature. It is a full orchestral sound that is steeped in the musical traditions of the late 19th Century, making use of instruments such as the Celesta and Harp, with chord progressions that everyone now associates with the ethereal and otherworldly. I didn’t shy away from my instincts when it came to this type of thing.

The original Harry Potter film series has a rich history of brilliant music, including of course Patrick Doyle’s score for ‘Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire’. How did you put your own mark on this new audiobook?

While I was very conscious of the musical history of the Harry Potter, I was most certainly offered the opportunity to let my own musical voice come through. As someone who grew up reading the books, watching the films, playing the video games, and even sitting in on the recording sessions at the age of 14; I have a genuine fondness for everything Harry Potter, especially its music. Getting the opportunity to contribute some of my own music to the canon was a privilege, and hopefully the listeners will enjoy hearing a whole host of new musical themes inspired by the subjects of study at Hogwarts.

It’s been an exciting year – could you tell us a bit more about what’s next in the pipeline for you?

I am currently creating a score for the Prague Shakespeare Company production of a new play entitled Masaryk in America, being performed on November 15th at the Prague Estates Theatre – the same theatre that Mozart’s Don Giovanni premiered. It is the story of how the historically influential leader, Tomáš Masaryk, took guidance during his time in America and pioneered the formation of the democratic state of Czechoslovakia, to which he became its first President. I have had a great time working with PSC on a variety of productions over the past few years, and when discussing a new score for this play it felt strange not to discuss incorporating the music of the great Czech composers. So instead of composing brand new music, I am going about producing new arrangements for string quartet of the music of figures such as Dvořák and Smetana, in order to produce a score that has its own connotations to a Czech audience and includes musical pieces that Masaryk himself was likely very fond of.

Thanks so much Patrick! The ‘Nae Pasaran’ soundtrack is available across all digital platforms now on Air-Edel Records.